Tetris Rotations

Implementing a Tetris clone is a popular first project for aspiring game developers. The rules are simple enough, but implementing the rotations requires some thought. The obvious approach, most programmers would think of first, is to represent the pieces as two-dimensional arrays. You could then do the rotations manually and save the results in a lookup-table or rotate the pieces using some form of rotation algorithm.

Pre-computing the rotations and storing them in a lookup-table is a good idea, because as I will explain later, some desirable features of the rotations can only be achieved by shifting the piece after rotation. However, generating the lookup-table manually is not very maintainable. In the remainder of this article I will first derive a general rotation algorithm from rotation matrices. Then I will show how this algorithm can be used to generate lookup-tables for more fine-tuned rotation systems.

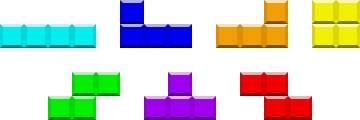

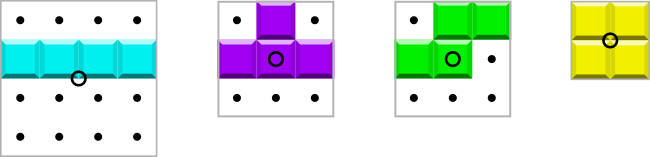

Figure 1 above shows the seven Tetrominos. From now on I will refer to each piece by a capital letter resembling its shape, i.e. I, J, L, O, S, T and Z. I will not represent the pieces as two-dimensional arrays, but as lists of four coordinates each. This simplifies rotation and collision detection, because I only have to consider the four relevant coordinates of each piece instead of all the elements of a two-dimensional array. For example the initial orientation of the I-piece, as shown in figure 2 below, is represented as [(0, 1), (1, 1), (2, 1), (3, 1)].

Two things are worth mentioning about this representation. Firstly, I don’t use a Cartesian coordinate system, but the usual screen coordinates, starting with (0, 0) in the top left. This makes drawing the piece easy. Secondly, each piece is assumed to live in a square bounding-box, the center of the box being the center of rotation.

A General Rotation Algorithm

The first rotation system I will discuss is called “Super Rotation System” (SRS). This is the system currently endorsed by The Tetris Company. It does not rely on any orientation dependent shifting, which makes it a good starting point for us. The initial orientations of the pieces are shown in figure 2. Note, that all pieces start with their flat sides facing down.

From linear algebra we know that the general form of a matrix for clockwise rotation around the origin, in two dimensions, by an angle \(\theta\) is:

\[R = \begin{pmatrix} \cos \theta & \sin \theta \\\ -\sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{pmatrix}\]Because in our case we can calculate all rotations by repeatedly rotating by 90°, this simplifies to:

\[R = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\\ -1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\]However, this matrix assumes Cartesian coordinates. To use screen coordinates, we have to account for the flip of the y-axis. The rotation matrix then becomes:

\[R = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\]To rotate a coordinate we would multiply it with this matrix, but we can translate the multiplication into simple assignments:

x_new = -y_old

y_new = x_old

Next, to rotate around a pivot-point, instead of the origin, we have to do some shifting. Before rotating, we have to shift the coordinates so that the pivot-point becomes the origin (this shift is called sb below) and shift them back after rotating (called sa below):

x_new = sa_x + (y_old - sb_x)

y_new = sa_y - (x_old - sb_y)

Normally we would have sb = sa, but for Tetrominoes the pivot-point is sometimes on the grid between two cells (for the I- and O-pieces) and sometimes at the center of a cell (for all other pieces).

Because we assumed the pieces live in a bounding-box, whose center is the center of rotation, it turns out that

sa_x = 1

sb_x = size - 2

sa_y = 0

sb_y = 0

where size is the size of the bounding-box (i.e. 2, 3, or 4), works for all blocks. So to summarize, we get:

x_new = 1 - (y_old - (size - 2))

y_new = x_old

Assignments for counter-clockwise rotation are similar, but if we cache the coordinates for all for piece orientations we will only need one direction.

Fine-tuned Rotation Systems

Apart from the SRS, many other rotation systems for Tetris exist and they vary in sophistication. For most of those rotation systems other values of the shift variables will work, but you might have to shift the piece again after rotation, depending on the resulting orientation of the block.

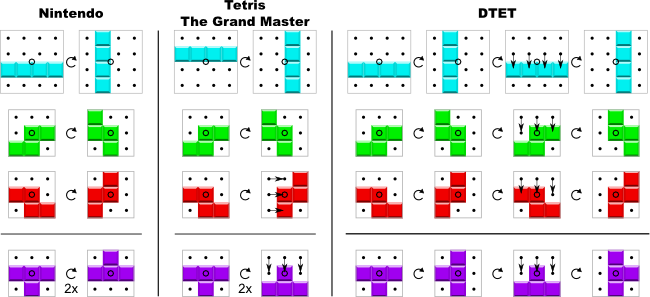

For example, the rotation system of Tetris for the NES (marked Nintendo in the figure below) has only two orientations for most blocks – the original orientation and the result of rotating the block clockwise by 90 degrees. “Tetris The Grand Master” – a version of Tetris designed with highly skilled players in mind – shifts some blocks after rotating. Specifically it shifts the Z-Block to the right after rotation (effectively the same as rotating it counter-clockwise) and it shifts the T-block down to keep the current height of the falling block independent from its orientation.

The DTET rotation system provides four orientations instead of just two, but also shifts most blocks down after rotating by 180 degrees to keep them from “jumping up”.

Where To Go From Here

As you see implementing basic Tetris rotations is not that hard. However, if you want an implementation that works well even for very skilled players you will have to put some more thought into it. If you want to know more about the technical details of popular Tetris implementations you can find many interesting articles on this wiki. I hope you have fun implementing your own Tetris clone.